Maggie Nevala ’26

Damage to Anchorage’s downtown after the 1964 earthquake

Alaska is a state that is constantly on the brink. Earthquakes are a daily occurrence, barely warranting rousing awake, the 7.1 quake of 2018 only closing school for a week before students returned to classrooms with cracks in the walls. But in 1964, the 9.2 Great Alaskan earthquake thoroughly upended the growing city of Anchorage. The homes and infrastructure that were largely unequipped for such a disaster were destroyed, the death toll rising as the state experienced the aftershocks and effects that would continue for years to come. When Dorathy Bruce Farr arrived in Anchorage in 1965, the city was still rebuilding—and so was she.

Almost the entirety of the information that remains about Dorathy Bruce Farr can fit in one box, the papers enclosed largely consisting of the countless letters she sent to peers and the copious notes of the reporter who worked to find Dorathy after her location became unknown to her friends in the 1980s.

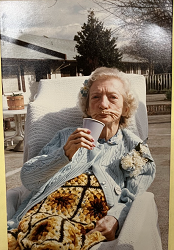

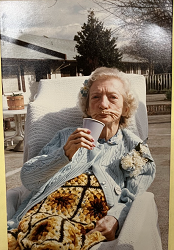

One of the few available photos of Dorathy Bruce Farr, taken after she was found in a care center in 1985

These pen markings and scribblings make up all that is known about Dorathy’s life, certain buzzwords sticking out among them all and illustrating her origins. She was born in Portland in 1904, married her first husband at 18 and had a son, and then married fellow artist Fred Farr in the 1930s. She and Fred moved to New York together, where they hobnobbed with other artists, he was commissioned to make murals, and she studied her craft and made a name for herself as a batik painter. It is after this period that the details get murky. There is nothing said about what happened to Dorathy’s relationship with Fred, but she returned to Portland alone, continuing to exhibit her work there but making a meager living from it. The ‘60s were a blur of art, parties, and internal struggles that ended in her last show in 1970.

Dorathy Bruce Farr is a woman of many mysteries, from her gradual mental decline due to what was most likely Alzheimer’s, the ambiguous death of her son, and the severance of any communication with her friends from 1980 to 1985, when she was found in a care center.

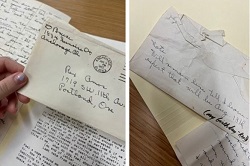

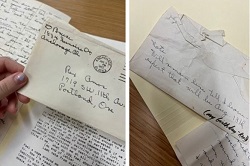

The front and back of one of the envelopes used to enclose the letters Dorathy Bruce Farr wrote to Rex Amos from Anchorage (Box: 1, Folder 3)

In all the many accounts of Dorathy’s adventures—or the attempts to piece them together—there is one that appears as a lone sentence, as an afterthought of an addition to a list of details about her: “Alaska ‘65 = work fish cannery” (Box: 1, Folder: 19) , or “She worked half a year in an Alaska salmon cannery” (Box: 1, Folder: 22). These are small descriptors used for a larger-than-life place, a place that should not slip through the cracks so easily. Even knowing her financial motivations for the trip—Dorathy was hoping to kick start her career by earning enough money to go back to New York—the lack of further details begs for there to be more to discover about Dorathy’s short and mysterious time spent in the Last Frontier, and a mere four letters written by her bear the burden of telling us the tale.

Each of the four letters—written to fellow artist Rex Amos in July and August 1965—provide a unique insight into Dorathy’s observations and thoughts about the state. In the first of the letters, she expounds on the imagery of the city with the appraising eye only a seasoned painter could have. She creates a contrast between the beautiful nature surrounding her—“the mountains are purple, black, and sapphire and the sun is shining down the valleys” (Box: 1, Folder: 1)—with what she sees as the disruptive expansion of the cityscape. Her poetic musings are interrupted by the telltale sounds of suburbia: lawn mowers, station wagons, taverns, Tastee Freezes. Dorathy shuns these modes of innovation, referring to Anchorage in one of her first letters as a “dull, ugly, grimy, hideous stereotype of a city.” (Box: 1, Folder: 1).

An early, 1950s Tastee Freez in Anchorage, like the one Dorathy describes in her letters as a sign of suburbia

Harsh words aside, here in 1965, she pinpoints the dichotomy lived by many Alaskans today, how the gray urban world encroaches on the natural one, how mountains loom over the skyline of a downtown that is not much of an expansive downtown at all. But for many of the current generation living there, it is the only city they have ever known, and that is what Dorathy was unequipped to realize during her brief excursion—that a place that appears contradictory to her, where history and wilderness and urbanization live side by side, was and is a home to many. But in her last letter, where she celebrates her upcoming return to the Lower 48, she encapsulates Anchorage best in one phrase: “The Greatest Little Big Town in Alaska.” (Box: 1, Folder: 4). Residents of the largest state by area in the U.S. are well-aware that often running into someone you know is as easy as turning the corner.

While Dorathy never directly references the earthquake that happened in Alaska the year prior, her observations about the city’s urban developments reflect the recovery efforts that were still ongoing. And there are many other instances in the letters where she places her time there in a historical context. To make money to fund future travels, Dorathy works in a salmon cannery, presumably in the coastal fishing town of Ketchikan that is mentioned in passing in the letters.

This endeavor was common for 20th century Alaskan teenagers looking to make some extra cash—a traditional practice that has evolved into families who commercial fish every summer. Additionally, Dorathy’s second letter to Rex Amos consists almost entirely of newspaper clippings that provide an inside look into this world, the articles excerpted referencing Alaska’s significance in the Vietnam War, a still prominent banking chain, and a senator whose name is now emblazoned on one of Anchorage’s ten middle schools.

Newspaper clippings included in one of Dorathy Bruce Farr’s letters from Anchorage (Box: 1, Folder: 2)

With these clippings and notes, Dorathy immersed herself in the culture of a city that would continue to be relevant beyond the time of her stay, possibly without even realizing she did so.

Dorathy Bruce Farr’s letters from Anchorage can only provide so much information about her months there, but by considering the historical scene at the time and taking in the picture she paints of the landscape, we can place ourselves in her shoes and into the image of an Anchorage both past and present. In 1965, Dorathy was entering the last phase of her career as an artist, and all this happened against the backdrop of a state only six years old, when the land was shiny and fresh and was a place where one could pursue adventure, set down roots, and start anew.

Sources

Correspondence, 1965 July 2, Series I, Box: 1, Folder: 1. The Dorathy Bruce Farr

papers, WUA027. Willamette University Archives and Special Collections.

Correspondence, 1965 July, Series I, Box: 1, Folder: 2. The Dorathy Bruce Farr

papers, WUA027. Willamette University Archives and Special Collections.

Correspondence, 1965 August 2, Series I, Box: 1, Folder: 3. The Dorathy Bruce

Farr papers, WUA027. Willamette University Archives and Special

Collections.

Correspondence, 1965 August 9, Series I, Box: 1, Folder: 4. The Dorathy Bruce

Farr papers, WUA027. Willamette University Archives and Special

Collections.

Various reviews of art shows, 1965-1970, Series II, Box: 1, Folder: 19. The

Dorathy Bruce Farr papers, WUA027. Willamette University Archives and

Special Collections.

Photographs, notes, draft of article and copy of Northwest Magazine with the

article, 1985 June 23, Series II, Box: 1, Folder: 22. The Dorathy Bruce Farr

papers, WUA027. Willamette University Archives and Special Collections.

According to Merriam-Webster, autumnity can be defined as the “quality or condition characteristic of autumn.” In other words, it’s that time of the year when the days are often beautiful and warm, but the nights and mornings are cool and crisp. There is occasional rain, but it’s refreshing and exciting rather than tiresome and never-ending. The leaves on the trees are turning beautiful colors, geese are honking through the skies in great numbers, pumpkin spice is everywhere, and a good cup of hot coffee or an amazing tea latte brings serious joy. It’s the season of apple cider donuts and harvest festivals, falling acorns and scrambling squirrels, flannel sheets and cozy sweaters…

According to Merriam-Webster, autumnity can be defined as the “quality or condition characteristic of autumn.” In other words, it’s that time of the year when the days are often beautiful and warm, but the nights and mornings are cool and crisp. There is occasional rain, but it’s refreshing and exciting rather than tiresome and never-ending. The leaves on the trees are turning beautiful colors, geese are honking through the skies in great numbers, pumpkin spice is everywhere, and a good cup of hot coffee or an amazing tea latte brings serious joy. It’s the season of apple cider donuts and harvest festivals, falling acorns and scrambling squirrels, flannel sheets and cozy sweaters… Summer stretches out before us in all its glory—light-filled days, warm evenings, beautiful blooms, fresh fruits and vegetables, outdoor time, vacation travels—all the simple joys of summertime life. Summer offers us the chance to relax a little, soak up the sun, enjoy long conversations with family and friends, stroll aimlessly through gardens and parks, lounge by pools and lakes, and explore other places near and far. And what better way to celebrate sunny days and mild nights than by immersing ourselves in the captivating world of books? The longer days beckon us to tackle that long list of books we’ve been meaning to read, to escape into different worlds, explore different perspectives, lose ourselves in exciting mysteries, and learn something new. No matter what your plans are for the summer, a good book is a perfect companion. To get you started on your reading adventures, check out these summer-related titles available from the library’s collection on the

Summer stretches out before us in all its glory—light-filled days, warm evenings, beautiful blooms, fresh fruits and vegetables, outdoor time, vacation travels—all the simple joys of summertime life. Summer offers us the chance to relax a little, soak up the sun, enjoy long conversations with family and friends, stroll aimlessly through gardens and parks, lounge by pools and lakes, and explore other places near and far. And what better way to celebrate sunny days and mild nights than by immersing ourselves in the captivating world of books? The longer days beckon us to tackle that long list of books we’ve been meaning to read, to escape into different worlds, explore different perspectives, lose ourselves in exciting mysteries, and learn something new. No matter what your plans are for the summer, a good book is a perfect companion. To get you started on your reading adventures, check out these summer-related titles available from the library’s collection on the  The academic year is winding down, and oh, what a year it has been! After months of living the college life in all its hectic glory, summer break is near. For many of us, that means the chance to relax, unwind, and maybe finally get enough sleep for a change! Quality sleep is absolutely critical for overall health and well-being, but during the whirlwind of an academic year, it is often hard to prioritize sleep. What better time to work on developing good sleep habits then during the month of May when we celebrate Better Sleep Month! Take advantage of this awareness month by paying attention to your sleep environment and routines, being aware of how diet and exercise play a role in sleep quality, and learning more about sleep health in general. And to help you in your exploration of sleep, check out one of the sleep-related books from the library’s collection featured on the

The academic year is winding down, and oh, what a year it has been! After months of living the college life in all its hectic glory, summer break is near. For many of us, that means the chance to relax, unwind, and maybe finally get enough sleep for a change! Quality sleep is absolutely critical for overall health and well-being, but during the whirlwind of an academic year, it is often hard to prioritize sleep. What better time to work on developing good sleep habits then during the month of May when we celebrate Better Sleep Month! Take advantage of this awareness month by paying attention to your sleep environment and routines, being aware of how diet and exercise play a role in sleep quality, and learning more about sleep health in general. And to help you in your exploration of sleep, check out one of the sleep-related books from the library’s collection featured on the  April in Oregon is an exciting time of the year, complete with wild weather, bursting blossoms, and frolicking ducks and geese. The whole natural world awakens with new growth and new life. As thrilling as this revitalization is, April is exciting for another important reason–it’s National Poetry Month! In 1996, the Academy of American Poetry (AAP) proclaimed April as National Poetry Month and poetry lovers have been celebrating this month ever since. According to AAP, their goals for the month include an effort to “highlight the extraordinary legacy and ongoing achievement of American poets” and “encourage the reading of poems.” So while you’re out appreciating the wonders of spring, why not take a moment to appreciate the wonders of poetry? Take a look at our

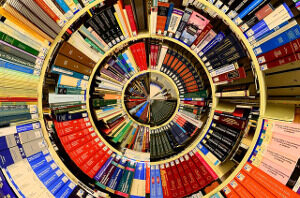

April in Oregon is an exciting time of the year, complete with wild weather, bursting blossoms, and frolicking ducks and geese. The whole natural world awakens with new growth and new life. As thrilling as this revitalization is, April is exciting for another important reason–it’s National Poetry Month! In 1996, the Academy of American Poetry (AAP) proclaimed April as National Poetry Month and poetry lovers have been celebrating this month ever since. According to AAP, their goals for the month include an effort to “highlight the extraordinary legacy and ongoing achievement of American poets” and “encourage the reading of poems.” So while you’re out appreciating the wonders of spring, why not take a moment to appreciate the wonders of poetry? Take a look at our  The big celebration in February is Valentine’s Day but did you know there is another huge cause for celebration? February is Library Lovers’ Month—a whole month dedicated to celebrating the place that so many of us hold near and dear to our heart! Libraries are spaces devoted to many wonderful concepts such as cultural preservation, freedom of information, and lifelong learning. They provide access to great collections of books, journals, video recordings, archival treasures, and more. Libraries also offer a place for people to socialize, work together on projects, and enjoy special exhibits; they provide a quiet, safe space for reflection and for community. Some libraries, like the Hatfield Library, extend access to unexpected things such as jigsaw puzzles, craft materials, home improvement items, and much more. And, of course, libraries offer intelligent, dedicated staff, ready to help you! Join us this month in celebrating all the great libraries out there—past, present and future!

The big celebration in February is Valentine’s Day but did you know there is another huge cause for celebration? February is Library Lovers’ Month—a whole month dedicated to celebrating the place that so many of us hold near and dear to our heart! Libraries are spaces devoted to many wonderful concepts such as cultural preservation, freedom of information, and lifelong learning. They provide access to great collections of books, journals, video recordings, archival treasures, and more. Libraries also offer a place for people to socialize, work together on projects, and enjoy special exhibits; they provide a quiet, safe space for reflection and for community. Some libraries, like the Hatfield Library, extend access to unexpected things such as jigsaw puzzles, craft materials, home improvement items, and much more. And, of course, libraries offer intelligent, dedicated staff, ready to help you! Join us this month in celebrating all the great libraries out there—past, present and future!

This month brings us the joy of winter break and various holidays–many of us will be gathering with family and friends for delicious homecooked meals and tasty sweet treats. There is something magical about cooking and baking in a warm, cozy kitchen when the weather outside is frightful. It doesn’t matter if we are making a new recipe or a traditional family favorite, sharing our scrumptious creations with our loved ones is a highlight of the season. Whether you’re a veteran chef or a novice baker, why not find out more about cooking and baking with one of these books from the library’s collection featured on the

This month brings us the joy of winter break and various holidays–many of us will be gathering with family and friends for delicious homecooked meals and tasty sweet treats. There is something magical about cooking and baking in a warm, cozy kitchen when the weather outside is frightful. It doesn’t matter if we are making a new recipe or a traditional family favorite, sharing our scrumptious creations with our loved ones is a highlight of the season. Whether you’re a veteran chef or a novice baker, why not find out more about cooking and baking with one of these books from the library’s collection featured on the  The weather is getting colder and the days are getting shorter and many of us relish the opportunity to stay inside with a good book and a hot beverage of our choice. This time of year, we look forward to Fall break, a few days off, good food, and some time with family and friends. But the unhoused or homeless experience is very different as they struggle to stay warm, dry, fed, and hopeful. Did you know 5 percent of homeless people in the United States are unaccompanied youth under 25? And Oregon has one of the highest rates of homelessness in the country. November is National Youth Homelessness Awareness Month so take some time to learn more by taking a look at some of these books from the library’s collection featured on the

The weather is getting colder and the days are getting shorter and many of us relish the opportunity to stay inside with a good book and a hot beverage of our choice. This time of year, we look forward to Fall break, a few days off, good food, and some time with family and friends. But the unhoused or homeless experience is very different as they struggle to stay warm, dry, fed, and hopeful. Did you know 5 percent of homeless people in the United States are unaccompanied youth under 25? And Oregon has one of the highest rates of homelessness in the country. November is National Youth Homelessness Awareness Month so take some time to learn more by taking a look at some of these books from the library’s collection featured on the