Ryosuke Cohen and his involvement in the global mail art movement

By Emily Zuber ‘23

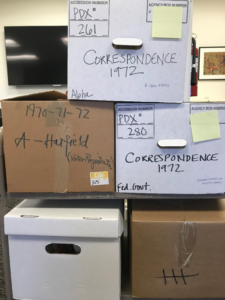

Sometimes when conducting research, it is unknown what will be found or which items will pique interest the most. As I dug through the Claudia Cave papers within the Mark O. Hatfield Library Archives learning about the wide world of mail art, I found a variety of artists’ pieces; specifically, a collage of colorful stamps from a Japanese mail artist. After reading the papers about him, I wondered: who is Ryosuke Cohen, and how did he become one of the leading figures in the history of the mail art movement in Japan? How did Claudia Cave, an artist from the Pacific Northwest, obtain his art? What is this artist up to now, and how has other mail art influenced his current work? In further research, I discovered some answers to these questions along with a better understanding of how mail art is adapting within the age of the Internet.

Ryosuke Cohen was born in 1948 and became an art teacher in Osaka, Japan. His early work consisted of traditional Japanese imagery mixed with contemporary styles until he was introduced to Western mail art in 1980 by his friend Byron Black. This art intrigued Cohen, because, according to him at that time, “Japan is known only for the classics, like Kabuki, Noh plays, bonsai plants, Zen…People misunderstand that the exhibitions in the authorized gallery are the best works.” The mail art movement consists of materials like stamps, collages, paintings, postcards, intricately decorated envelopes, newspapers, etc. that can be sent to a plethora of other artists who may choose to keep it, send it to another, or add onto the piece and return it. In the archives, I found that Claudia Cave even had multiple eggs with a stamp on it, so it is assumed that this ‘art’ can be interpreted freely by all; this freedom is what enticed Cohen to create and continue creating a variety of mail artwork.

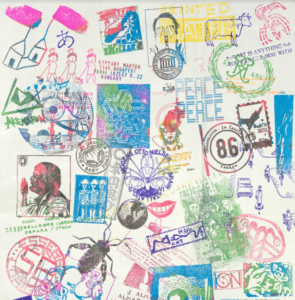

To participate in international mail art, Cohen began Brain Cell in 1985, which he continues with today. He explains that the reason why he titled this project Brain Cell is because “the structure of a brain seen through the microscope, with thousands of neurons grouped together and stratified, really resembles a diagram of the mail art network.” Using Gocco, a unique printing process for Japanese greeting cards, he creates a collage of logos, stamps, stickers, drawings, etc. on A3 paper. Then, he mails the result along with a list of addresses and a typed article to around 60 artists and keeps additional copies that are put into books. Cohen is said to have made 3 issues every month, now totaling over 1,000 Brain Cell papers. Unique materials are sent to him to be used for each issue so no two pieces are alike; all are different and made due to the wide array of images provided by other artists. This is perhaps how Cave was able to have 2 of the Brain Cell collages in her international mail collection. The cells I located inside the archives contain a wide array of images, including an insect, ocean landscape, bigfoot, ocean sunfish, Big Ben, the statue of liberty, random Hirigana letters and so on. The multiple ‘C’s found on some cells are Cohen’s signature stamp. These Brain Cell mail art papers are a unique assortment of art created by many artists from around the world and it is amazing just how many pieces Cohen has been able to create with his community.

Ryosuke Cohen had found widespread success in gaining participation from international artists, but it seems that the wonders of mail art in Japan had yet to be widely recognized. There had been a few Japanese postal artists who published works in Gutai magazine, though the publication died out in 1972. Ryosuke Cohen joined the Artists’ Union or Artists Unidentified (AU) in the ‘80s. This organization had a couple of Japanese postal artists at the time, like On Kawara, who is known for his postcard and contemporary art. Eventually, Cohen was able to collect work for exhibits at the Tokyo Metropolitan Museum, the Osaka Contemporary Art Center and the Kyoto City Museum. Though, it seems it would not be until later that he himself would travel outside of Japan.

In 2001, Cohen began his next art collection, The Fractal Portrait Project. With these works, he would travel to meet those who contributed to Brain Cell, including artists in the U.S., Italy, Korea, Holland, Belgium, England, and more. He would meet his correspondents and have them lay down on the Brain Cell papers where he would trace their silhouette in ink. Afterward, he draws a side-view portrait of their faces on smaller Brain Cell paper. Once finished, both pieces would be given to the artist. Cohen had to pause in 2010 due to cancer, but he continued the project until 2019. I found that since the pandemic began, he has been sending Brain Cell mail art. The latest piece is shown on his Facebook page as people tag him in posts thanking him for sending it to them. Unfortunately, he is unable to send any art to Ukraine at this time in 2022 due to the ongoing conflict with Russia.

In 2001, Cohen began his next art collection, The Fractal Portrait Project. With these works, he would travel to meet those who contributed to Brain Cell, including artists in the U.S., Italy, Korea, Holland, Belgium, England, and more. He would meet his correspondents and have them lay down on the Brain Cell papers where he would trace their silhouette in ink. Afterward, he draws a side-view portrait of their faces on smaller Brain Cell paper. Once finished, both pieces would be given to the artist. Cohen had to pause in 2010 due to cancer, but he continued the project until 2019. I found that since the pandemic began, he has been sending Brain Cell mail art. The latest piece is shown on his Facebook page as people tag him in posts thanking him for sending it to them. Unfortunately, he is unable to send any art to Ukraine at this time in 2022 due to the ongoing conflict with Russia.

It astonished me to learn about the vast amount of art Ryosuke Cohen has produced within the last 40 years in collaboration with tons of artists all over the world. From fellow artists in Osaka to Claudia Cave, these collages of art in Brain Cell and The Fractal Portrait Project continue to be created and seen by many. Even today, the Japanese mail artist states on his website that “Mail Art is far from finishing,” and that the multiple methods of correspondence in the digital age gives way to a diversity of participation within the mail art movement. This is especially true in a world currently facing a global pandemic where people seek connections with loved ones online. I am intrigued to see what Cohen & fellow mail artists will be creating in the future. It seems that we will see a larger increase in younger postal artists via the era of the Internet where reaching out to numerous contributors is extremely easy and I look forward to how it will evolve further.

Resources

Baroni, Vittore. The Neural Collages of Ryosuke Cohen. Artpool, https://artpool.hu/MailArt/chrono/1998/BrainCell.html.

Cohen, Ryosuke. Mail Art – Brain Cell – fractal (1997). Artpool, https://artpool.hu/MailArt/chrono/1998/BrainCell3.html.

Cohen, Ryosuke. Mail Art – Brain Cell – fractal (1999). Artpool, https://artpool.hu/MailArt/chrono/1998/BrainCell4.html.

Cohen, Ryosuke. Ryosuke Cohen Official Site. http://www.ryosukecohen.com/.

Held, John, Jr. Interview with Ryosuke Cohen from the National Art Center In Tokyo, Japan. SFAQ / NYAQ / LXAQ. 19 October 2012. https://www.sfaq.us/2012/10/interview-withryosuke-cohen-from-the-national-art-center-in-tokyo-japan/.

Held, John, Jr. Japanese Mail Art, 1956-2014. SFAQ / NYAQ / LXAQ. 8 September 2014. https://www.sfaq.us/2014/09/japanese-mail-art-1956-2014/#:~:text=Mail%20art%20remains%20a%20means,Association%2C%20continued%20with%20participation%20in.

International mail art, 1983-2016, Subseries A, Box: 3, Folder: 1. Claudia Cave papers, WUA118. Willamette University Archives and Special Collections.

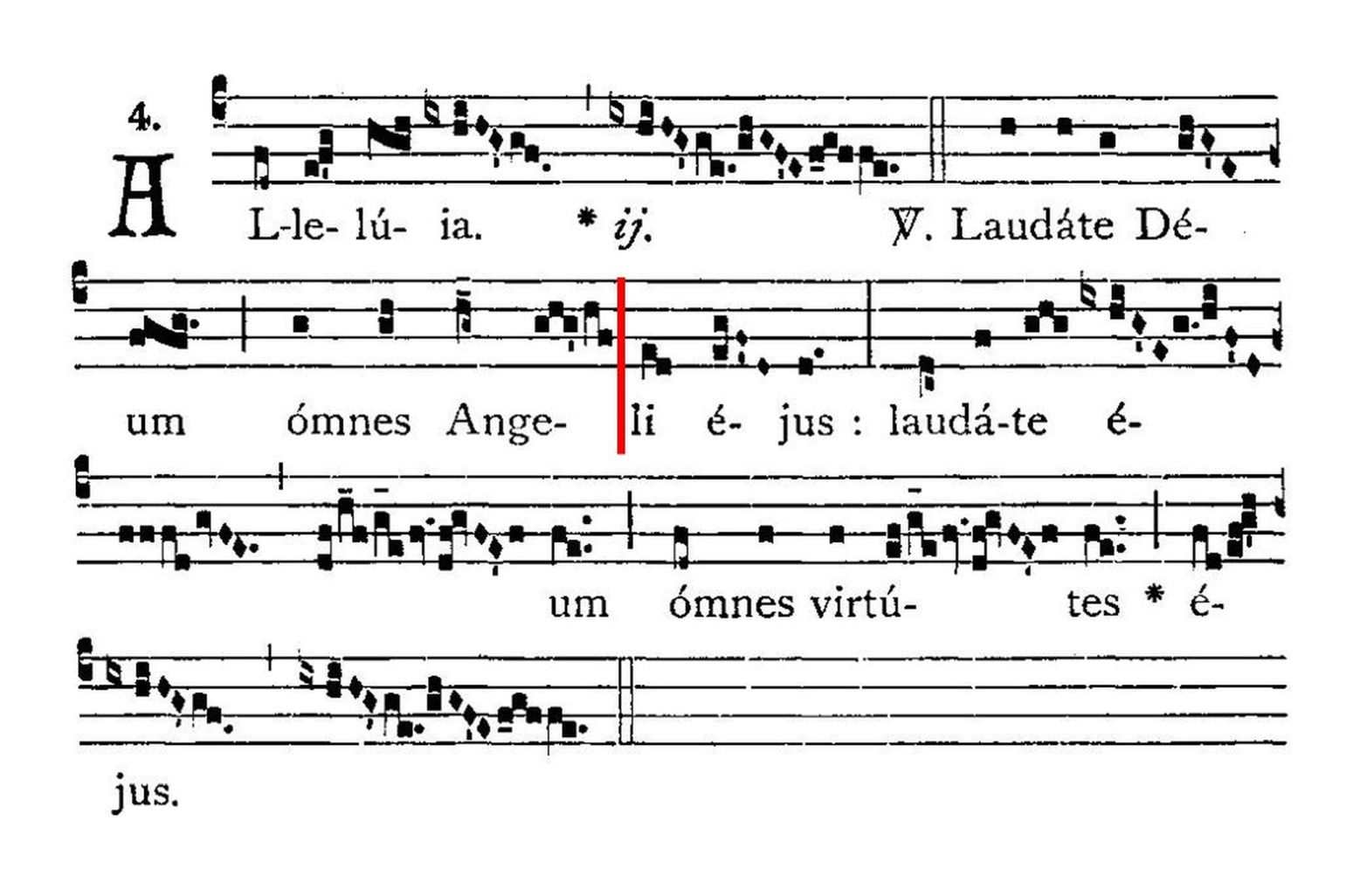

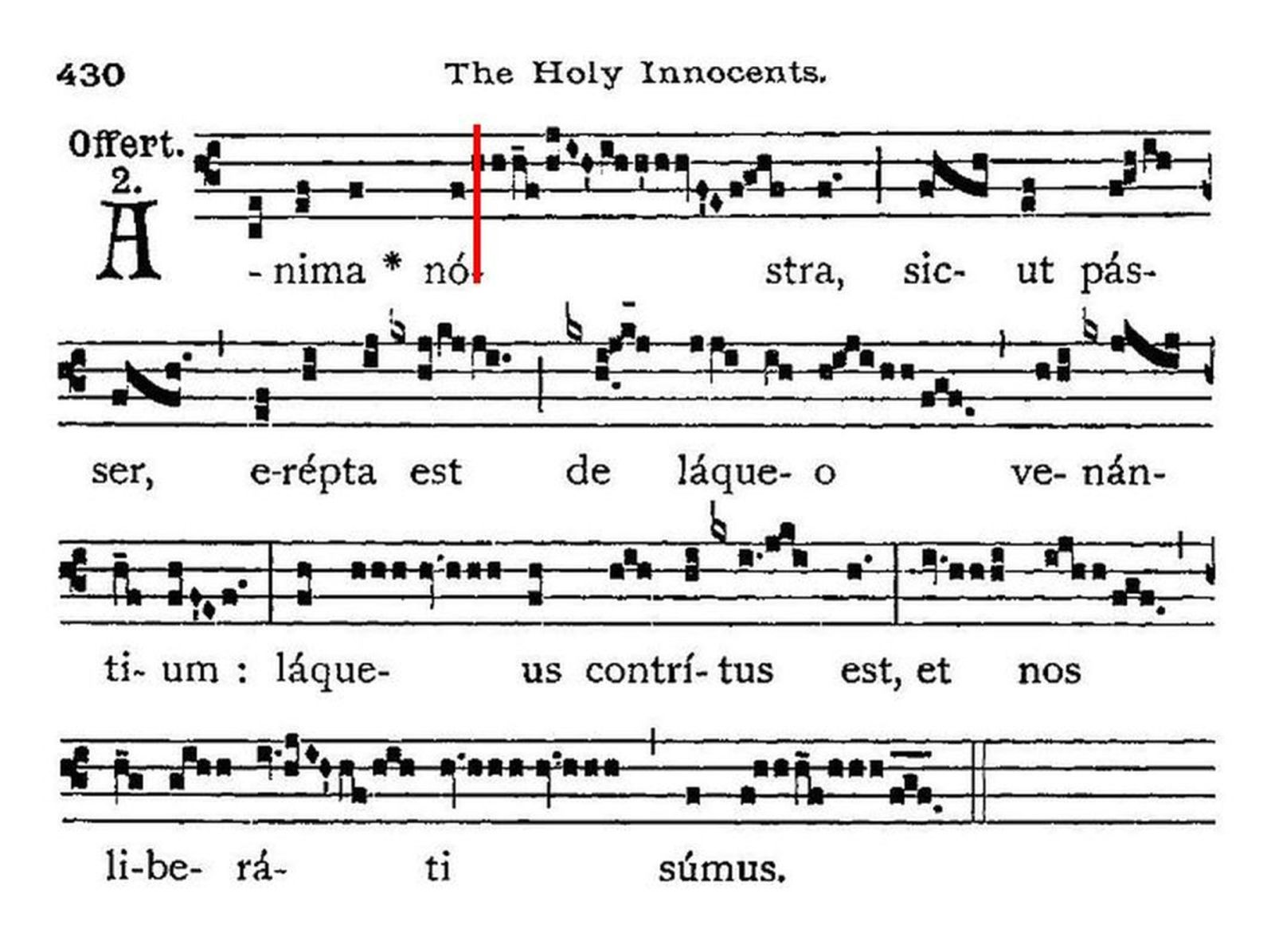

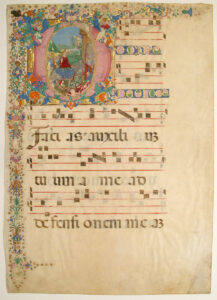

Identifying the Texts:

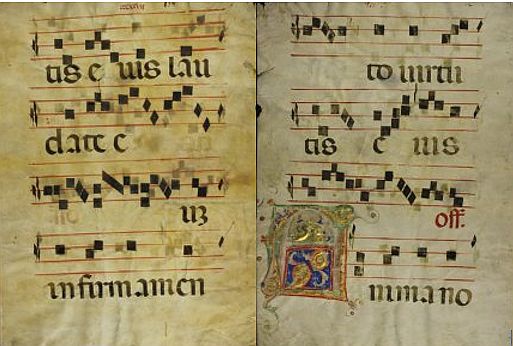

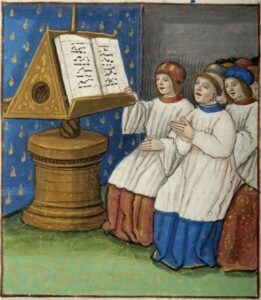

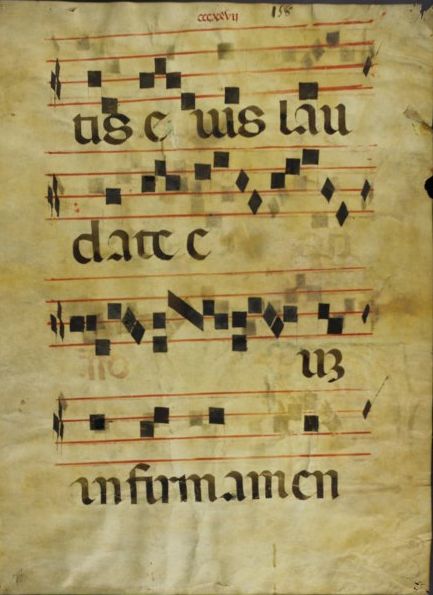

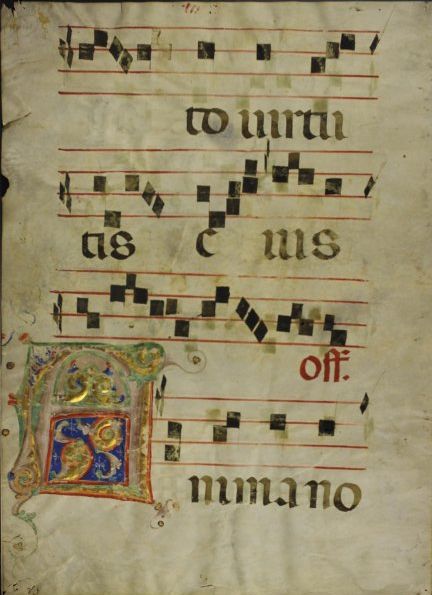

Identifying the Texts: Psalm 150, Verse 1 (King James Version) Praise ye the Lord. Praise God in his sanctuary: praise him in the firmament of his power.

Psalm 150, Verse 1 (King James Version) Praise ye the Lord. Praise God in his sanctuary: praise him in the firmament of his power.