By: Sarah Samala, ‘28

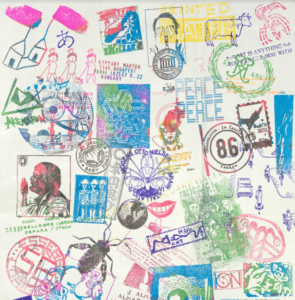

When you think of ballet, what comes to your mind? For most, it’s pink tights, pale tutus and classical music. However, when I was going through the materials donated by visual artist Tom Cramer in the Pacific Northwest Artists Archive, I came across the bright, almost psychedelic backdrops and hand-painted costumes of Oregon Ballet Theatre’s Jungle. Seeing Cramer’s strange, pop-art-esque art that typically covered cars or carved wood totems adorn the bodies and stage of the Oregon Ballet Theatre brought to mind several questions. Why was Tom Cramer chosen to set and costume a ballet? What was Jungle about? And finally, how did Cramer’s sets play into its narrative? Through research and the wealth of papers in the Willamette University Archives, I discovered the history of Jungle, and why Tom Cramer’s art was essential to its role within the modern dance world.

Tom Cramer was born in 1960 in Portland Oregon. He earned his BFA at the Museum Art School, now known as the Pacific Northwest College of Art in 1982. Cramer often combined different cultural mediums in his art. His early work, which consisted of abstract art and hand-carved totems, took inspiration from a variety of techniques like traditional Native American wood-carving and German expressionism. Cramer’s bright and chaotic style even made it onto unconventional canvases, as evidenced by his painted Volkswagens. Tom Cramer’s art was loud and memorable, yet described as eerily dark and foreboding by many. It was these qualities that caught the eye of dance agent Alex Dubay, who reached out to the Oregon Ballet Theatre’s artistic director, James Canfield, and pushed the visual artist into the world of ballet and theatre.

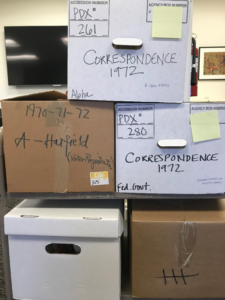

The Oregon Ballet Theatre first featured Cramer’s work in the 1994/95 season, where his first ever ballet set debuted in the American Choreographer’s showcase. The showcase was a culmination of several young choreographer’s original works, meant to challenge choreographers and dancers alike through its experimental nature. Shortly after being imbursed for this initial commission, Canfield sought out Cramer for another piece, one that would become one of Canfield’s most well-known works.

The 1996/97 season’s “James Canfield Signatures,” featured Jungle, a fast-paced piece meant to capture the violence and majesty of animal life. Unlike most productions, Jungle’s set, which was a thirty-by-sixty-feet mural that channeled the essence of nature in Cramer’s style, was actually created before the choreography. This unconventional choice challenged choreographers to mold their work around the energy of Cramer’s art, making it the foundation of the entire piece. The music used within Jungle was also an unusual choice; forms I, II, III and IV from Future Sound of London’s Lifeforms, uses ambient electronic sounds to mimic the bird and insect sounds of nature rather than carry the audience to a dramatic or climatic ending. The costumes reflect this unorthodox theme as well, instead of tailoring costumes to each dancer, Cramer painted a large piece of nylon in his colorful abstract style that was cut and sewn into the dancer’s outfits, meaning each costume carried a piece of the larger artwork. Some costumes were even painted directly onto the bodysuits while they were on the dancers.

3, Folder 2).

Aside from the American Choreographer’s Showcase, Jungle and its accompanying James Canfield Signatures were a modern first for the company, which typically produced traditional shows such as The Nutcracker and Romeo and Juliet. Similar to Cramer’s innovative method of combining different mediums, artistic director Canfield wanted Jungle to change the expectations of a “standard” ballet by merging the traditional art form with unconventional practices and abstract art. Throughout his work in the Oregon Ballet Theatre, Canfield strived to “carry ballet from one century to the next” (Box 2, Folder 2) and elevate the older artform for growing modern audiences. Cramer’s unique art served as the backbone for Canfield’s goal, and the contemporary Jungle became an important fixture within the Oregon Ballet Theatre’s history.

After its run in 1997, Jungle went on to fulfill its show’s title and become a James Canfield Signature, eventually being revived in 2002 as one of James Canfield’s final pieces before he left the company. Even today, Oregon Ballet theatre continues to stylize their performances. In the 24/25 season’s Hansel and Gretel, an eerie silent-film aesthetic was combined with gaudy and colorful sets, creating a sense of unease and like with Jungle, causing the production to visually stand out. Cramer went on to paint one more ballet set for Ballet Pacifica’s As is Us, which makes both his work at the Oregon Ballet Theatre and Ballet Pacifica nearly one of a kind. Though Cramer’s art strays toward wood reliefs more than painted murals nowadays, the production still stands as a crucial part of his legacy, and an important milestone in the modernization of the Oregon Ballet Theatre’s shows.

Works Cited

Cramer, Tom. Jungle 1997. Tom Cramer Art. https://www.tomcramerart.com/pages/jungle1.htm

Future Sound of London. Lifeforms, Virgin Records, 1994. Youtube,https://youtu.be/nhOXE4wn6Sk?si=X1oLslwk1oHe3EZ9.

Newspaper articles about art, 1986-2012, Subseries B, Box: 3, Folder: 3. Tom Cramer papers,

WUA122. Willamette University Archives and Special Collections.

Newspaper clippings (and exhibit fliers and correspondence to Betty Perkins (mother) and

Francesca Stevenson), circa 1979-2011, Subseries B, Box: 3, Folder: 2. Tom Cramer

papers, WUA122. Willamette University Archives and Special Collections.

Oregon Ballet Theatre booklets and fliers (season schedules), 1994-1997, Subseries A, Box: 2,

Folder: 10. Tom Cramer papers, WUA122. Willamette University Archives and Special

Collections.

Oregon Ballet Theatre. Oregon Ballet Theatre, https://www.obt.org/. Accessed 9 Mar. 2025.

Oregon Ballet Theatre “Spring Romance” (article about Tom Cramer), 1995 March 9 – March 12,

Subseries B, Box: 4, Folder: 5. Tom Cramer papers, WUA122. Willamette University

Archives and Special Collections.

Portfolio and resume, circa 2005-2009, Subseries D, Box: 3, Folder: 14. Tom Cramer papers,

WUA122. Willamette University Archives and Special Collections.