By Doreen Simonsen

Humanities and Fine Arts Librarian

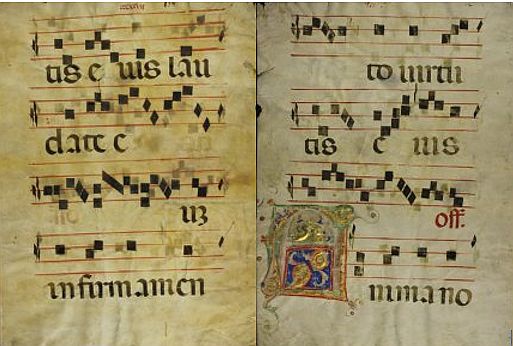

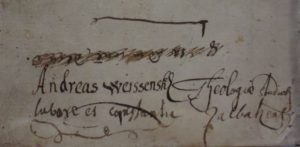

Somewhere in Europe in the 15th century, a choir sang an Alleluia followed by an Offertory on the Feast of the Holy Innocents on December 28th. A page from a book that contained parts of these songs was discovered last summer in the Vault of the Mark O. Hatfield Library. We do not know who donated this manuscript page to the library, but through the help of faculty members in the Music and Classical Studies Departments at Willamette University and elsewhere, we have been able to reveal its secrets and show how it relates to the holiday season.

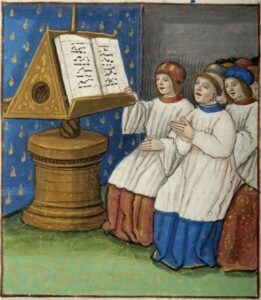

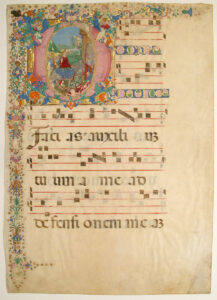

Psalter

France, Paris, between 1495 and 1498

MS M.934 fol. 141r

Morgan Library and Museum

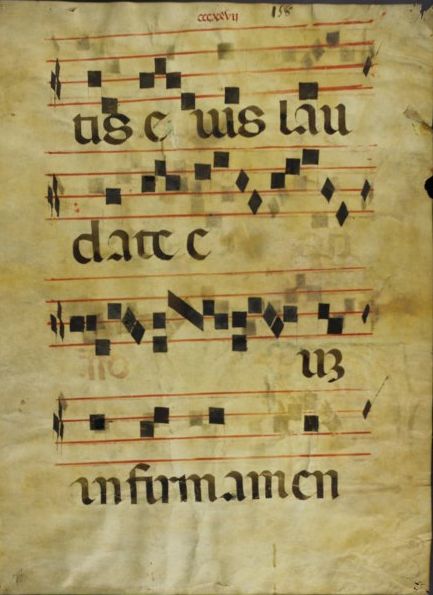

This large sheet of vellum (parchment prepared from animal skin) is 20 ⅞ inches high by 15 ⅔ inches wide and has neumatic (plainsong) notation on a four-line staff with texts in Latin. Chants are written in neumes, which are notes sung on a single syllable.

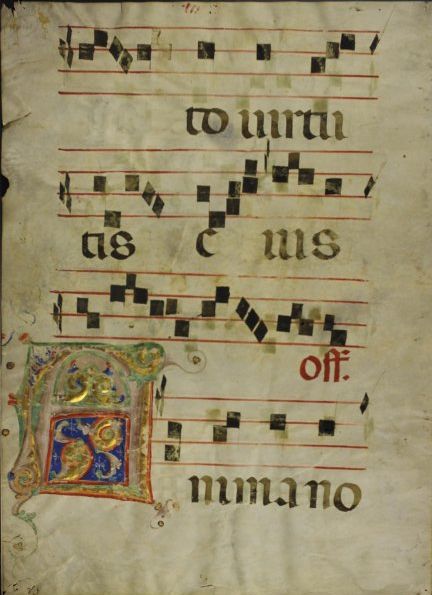

There is a large Illuminated initial in the lower left-hand corner of second page. (To see how this page and illumination was created, please watch this excellent video, Making Manuscripts, from the Getty Museum.) The reason for the large size of this page was that it was meant to be read by several members of a choir at one time. The expense of creating manuscript books meant that it would be more economical to create one large book for several people to use rather than several smaller books for each person in the choir to hold.

Here is an illustration from a Psalter (A book of Psalms) showing a group of clerics singing from a large book with musical notation, similar in size and format to our manuscript.

Identifying the Texts:

Identifying the Texts:

Professors Robert Chenault and Ortwin Knorr of Willamette University’s Department of Classical Studies identified the texts found on these two pages.

This first page (or recto page) contains the following words and word fragments:

…tis eius; laudate eum in firmamen-

And the second page (or verso page) contains the rest of the phrase:

to virtutis eius.

These phrases combine to form the end of this Bible Verse:

Alleluia. Laudate Dominum in sanctis eius; laudate eum in firmamento virtutis eius.

Psalm 150, Verse 1 (King James Version) Praise ye the Lord. Praise God in his sanctuary: praise him in the firmament of his power.

Psalm 150, Verse 1 (King James Version) Praise ye the Lord. Praise God in his sanctuary: praise him in the firmament of his power.

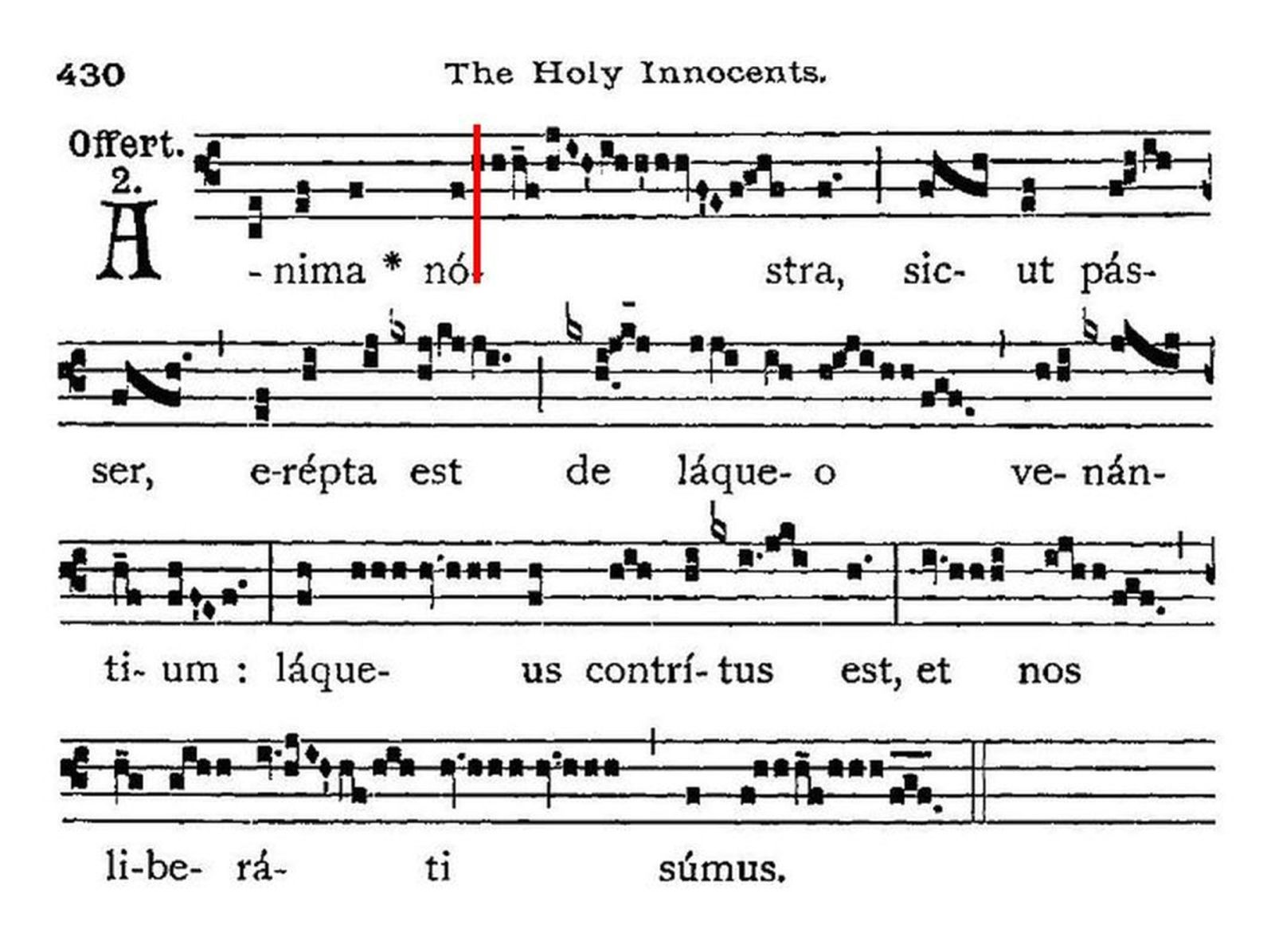

At the bottom of the second (verso) page, they identified the words: Anima no- which Dr. Richard Robbins (University of Minnesota-Duluth) identified as belonging to this verse:

Anima nostra sicut passer erepta est de laqueo venantium; laqueus contritus est, et nos liberati

sumus.

Psalm 123, Verse 7 (King James Version) Our soul is escaped as a bird out of the snare of the fowlers: the snare is broken, and we are escaped.

The two texts are separated by a red abbreviation of the word Offertory.

Identifying the Music

Professor Hector Aguëro of the Music Department at Willamette University shared images of our manuscript with his colleague Professor Richard Robbins, Director of Choral Activities at the University of Minnesota-Duluth and a scholar of choral music, especially Italian sacred music of the early Baroque.

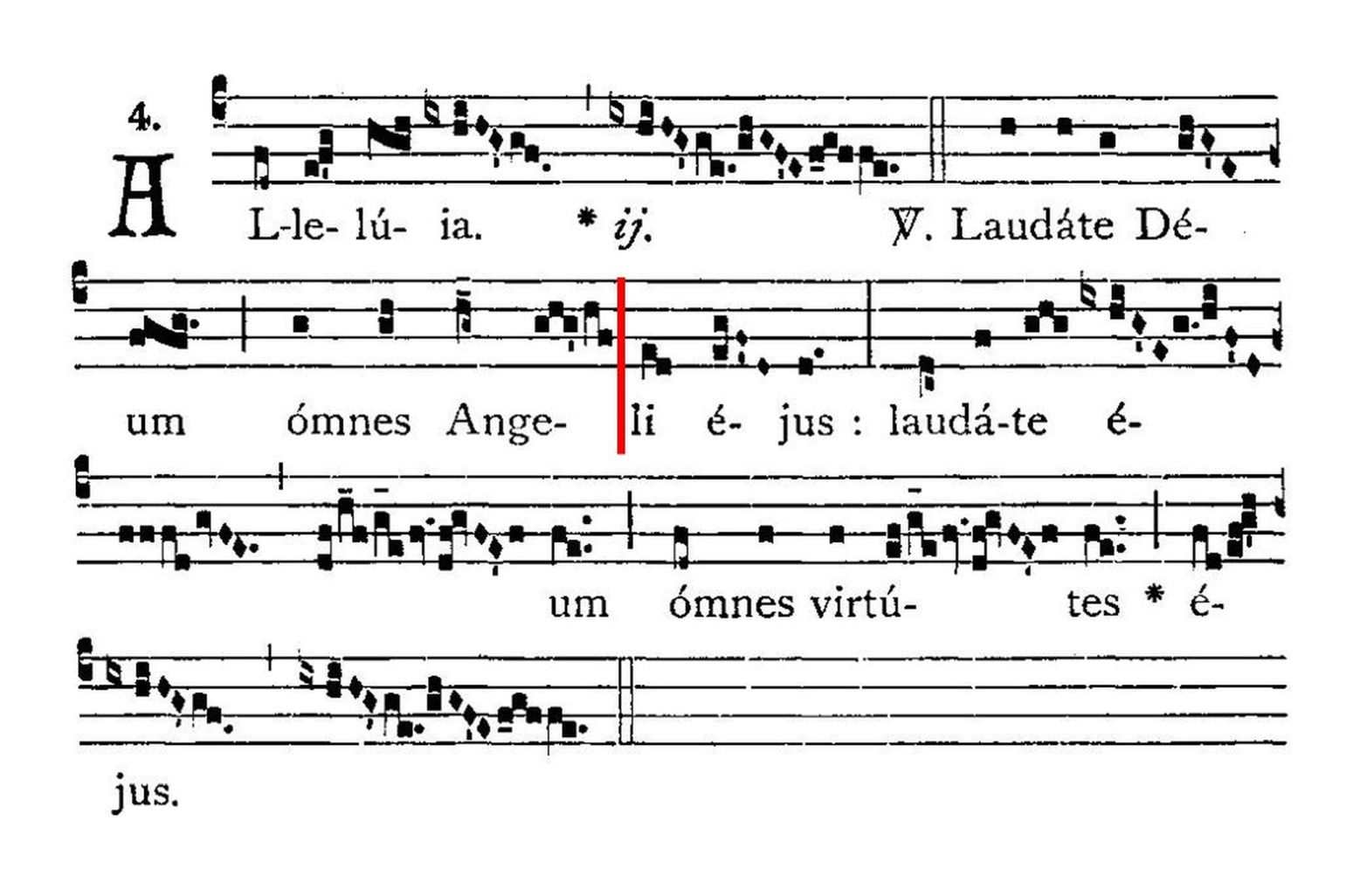

Dr. Robbins identified our manuscript as possibly being part of a Gradual, which is a book containing chants used in the Catholic Mass throughout the year. Robbins identified the first text and melody as the end of an alleluia verse, specifically Laudate Deum (mode IV). The second melody is an offertory on the text Anima Nostra (mode II).

Both of these chants can be found in the Liber Usualis, a book of commonly used Gregorian chants in the Catholic tradition.

The notation on the library’s manuscript starts at the red line in the Alleluia above, and it ends at the red line in the Offertory Anima No|stra below.

You can hear a performance and follow the texts of both chants here:

Alleluia, Laudate Deum

Offertory: Anima Nostra

The text of our missal differs from that of the Liber Usualis because of its early date. It was likely written in the 15th century, and, as Dr. Robbin explains, that means it was written before the Council of Trent (1545–63) codified the Catholic Mass and the order of the chants. There was a great deal of variety in Missals before the Council of Trent, so one cannot be sure when these melodies were used during the liturgical year. However, according to Dr. Robbins, these tunes match the tunes that appear in the Holy Innocents / Epiphanytide sections in post-Trent missals.

Dr. Robbins also pointed out that the illuminated letter A is ornate, which would have also been more appropriate for a Christmas use. The fancy illuminated letter A is probably also the reason we only have just one sheet from this gradual. These pages could contain ornate decorations and for this reason, they were frequently removed from graduals and treated as single artworks. Here you can see similar gradual pages from the Metropolitan Museum of Art. And this page shows the entry of Jesus into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday, all within the large initial D.

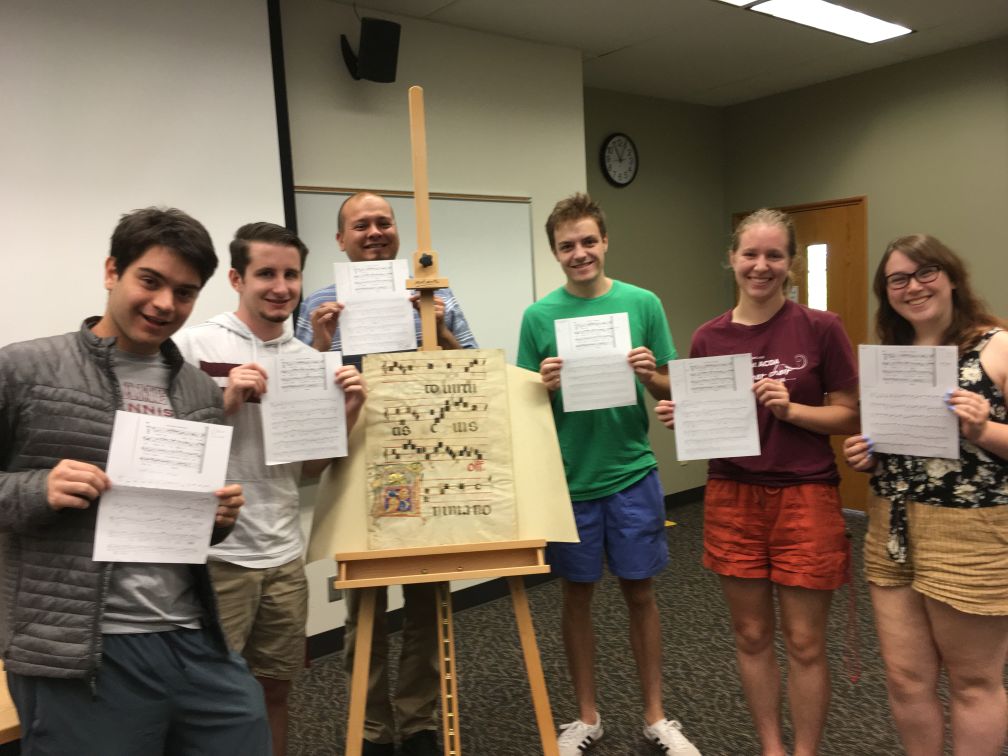

Teaching with a 15th Century Manuscript

The best thing about discovering this “new” manuscript in the vault was being able to share it with the students and faculty of Willamette University. In September 2019, as part of his Music History I course, Professor Aguëro had his Music History students transcribe the music written on the library’s Chant manuscript. Here you can see them displaying their work. It was such a delight to have students work with a manuscript from the library’s Rare Books Collection.

From left to right: Ethan Frank, Matt Elcombe, Professor Aguëro, Sam Strawbridge, Kate Grobey, and Sophie Gourlay

Acknowledgments

Many thanks to Professors Robert Chenault and Ortwin Knorr of the Department of Classical Studies and Professor Hector Aguëro of the Department of Music at Willamette University, and especially to Professor Richard Robbins, Director of Choral Activities at the University of Minnesota-Duluth. Their combined scholarship helped us explicate the text and illuminate the value and beauty of this seasonal manuscript.

Bibliography

Abbey of Solesmes. The Liber Usualis 1961. Internet Archive, http://archive.org/details/TheLiberUsualis1961. Accessed 27 Nov. 2019.

Anima Nostra Sicut Passer Erepta Est. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=2UrXb2QUSsI. Accessed 27 Nov. 2019.

“Bartolomeo Di Domenico Di Guido | Manuscript Leaf with Entry into Jerusalem on Palm Sunday in an Initial D, from a Gradual | Italian | The Met.” The Metropolitan Museum of Art, https://www.metmuseum.org/art/collection/search/469046. Accessed 27 Nov. 2019.

Chant Manuscript, ca. 15th Century. https://libmedia.willamette.edu/commons/item/id/163. Accessed 27 Nov. 2019.

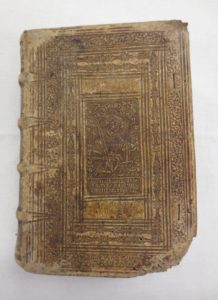

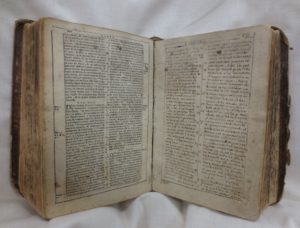

Council of Trent. Sacrosancti et œcumenici Concillii Tridentini Pavlo III, Ivlio III, et Pio IV, PP. MM. celebrati canones et decreta. Apud Cornab Egmond et Socios, 1644.

“Council of Trent | Definition, Summary, Significance, Results, & Facts.” Encyclopedia Britannica, https://www.britannica.com/event/Council-of-Trent. Accessed 27 Nov. 2019.

Gregorian Chant Notation. http://www.lphrc.org/Chant. Accessed 27 Nov. 2019.

Laudate Deum – Gregorian Chant, Catholic Hymns. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=kaVnBFhiwqU. Accessed 27 Nov. 2019.

Making Manuscripts. YouTube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=nuNfdHNTv9o&feature=youtu.be. Accessed 27 Nov. 2019.

Psalter, MS M.934 Fol. 141r – Images from Medieval and Renaissance Manuscripts – The Morgan

Library & Museum. http://ica.themorgan.org/manuscript/page/120/77003. Accessed 27 Nov. 2019

Robbins, Richard. “Re: Newly discovered 15th c. Chant manuscript.” Received by Hector Aguero, 22 Aug. 2019.