by Jess Kimmel

“Works of art are doorways to some unentered room. The artist is constantly knocking, demanding entry.”

~Carl Hall

Where does an artist’s story begin? Is it when, at the age of seven, they win $5 in their first newspaper art contest? Is it when they get caught sneaking into school after hours to make use of the art classroom? Perhaps when they send home pencil drawings from war, drawings of medical tents and dead soldiers? Any of these could be the defining moment of the first chapter in the life of Carl Hall, one of the most expressive and influential painters of the Pacific Northwest.

Yet buried deep in the research files of Roger Hull, who so diligently constructed a catalog of Hall’s life, lie a few unassuming photocopies of letters and statements bound together with a rusty paper clip. Dating from the 1940s, they detail the creation of Hall’s first painting of any note: Interlochen, Michigan. Having been assigned to process the Carl Hall series, these papers were a source of mild dismay to me. I only noticed them towards the end of the arrangement process, and they didn’t seem to fit neatly into the new categories that I had constructed. Perhaps that is why I was drawn to them, and why they are as good a place as any to begin the story of Hall’s career as an artist, which spanned over five decades.

Though he would eventually call the Willamette Valley his home, Carl Hall was born in 1921 in Washington, D.C., and grew up in Detroit. At sixteen, he received a scholarship to the Meinzinger Art School, where he studied under Carlos Lopez, a Cuban-American painting known for his New Deal murals.

Interlochen, Michigan, as shown in a magazine clipping found in the Carl Hall papers (Box 4, Folder 19)

Interlochen, Michigan was created by an eighteen year-old Hall in the summer of 1940, when he attended the National Music Camp in the painting’s namesake town. As the artist tells it, he was fishing in a stream one day when a log happened to float past him, teeming with a “small world of plant life.” It occurred to him that such a thing would make an interesting subject for a painting. While Interlochen’s Midwestern locale might seem a far cry from the Oregon landscapes that would later take front and center on Hall’s canvas, it bore many of the stylistic hallmarks that would remain with him: vivid dark colors, a visible interplay of wind and weather, and just enough pattern distortion to create an eerily romantic display of magic realism. Interlochen, Michigan, was first consigned to the Detroit Artists’ Market before being sold to the Boston Museum of Fine Arts in 1941.

In 1942, Hall underwent his military training at Camp Adair near Corvallis where he both met his wife Phyllis and fell in love with Oregon’s natural beauty. He described the state as “Eden Again,” and swore that he would settle there permanently if he survived World War II. He spent eighteen months on active duty in the Philippines and Japan before returning. Only a few months later, Carl and Phyllis Hall moved to Salem, where they would spend the rest of their lives. Not long after, Hall accepted a position as a professor of art at Willamette University. John Olbrantz, the first director of the Hallie Ford Museum of Art, later said that the history of Willamette’s art department would forever be tied to Hall, who taught here for thirty-eight years and made an impact on the lives of generations of artists.

Hall garnered national renown over his long career for his haunting and beautifully detailed panoramic views of Oregon’s countryside. Views that Roger Hull describes as “quilts of greens and yellows” and “mist, floating as ribbons in the branches of trees.” Despite this, Hall later began to shift his stylistic focus from realistic to abstract. Like other such abstractionists, he believed that art came closer to capturing the true essence of its subject with simplicity.

Last Shadow (1971), an example of Hall’s abstract work. Photo from the Carl Hall papers (Box 4, Folder 39)

Over time, clearly outlined features would become fleeting forms and patterns that revealed their inner nature, in an almost spiritual progression of imagery. Referring to Hall, gallery director Julie Larson wrote that “one of the hallmarks of a great artist is that their work evolves over time.” Carl Hall is nothing if not evolutionary.

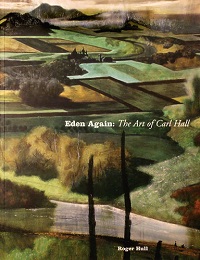

In the years leading up to and following Hall’s death in 1996, his colleague and longtime friend Roger Hull began conducting research for a monograph and retrospective exhibition on his life, titled Eden Again after Carl’s words for the muse that he found in Oregon. Eden Again was completed in 2001, a fitting tribute to the life of one of the Pacific Northwest’s most important creative figures, whose story began, in some part, with a log floating down a stream in Interlochen, Michigan.

Eden Again: The Art of Carl Hall by Roger Hull. Photo from the Roger Hull research files (Box 2, Folder 32)

Roger Hull’s research files on Carl Hall and other Pacific Northwest artists can now be found in the Willamette University Archives, where they were compiled in 2014. Hall’s series includes biographical information, research notes, reproductions of both his written and painted works, and many other items related to Hall’s life and family dating from 1941-2008. Nearly forty years of correspondence between the Hulls and the Halls is recorded, from the Christmas cards that Carl Hall sent to Roger and Bonnie Hull in the 1970s to letters detailing Willamette University’s continued acquisition of the artist’s inventoried works sold and donated by Phyllis Hall well into the 2000s.

Sources

Carl Hall, 1941-2008, Series II. Roger Hull Research Files on Pacific Northwest Artists, WUA065. Willamette University Archives and Special Collections.

Biographies and Resumes, Box: 2, Folder: 1.

Completed Monograph, 2000, Box: 2, Folder: 32.

General Correspondence, 1941-2007, Box: 2, Folder: 5.

Carl Hall papers, WUA124. Willamette University Archives and Special Collections.

“Interlochen”, 1940-1980, Subseries C, Box: 4, Folder: 19.

“Last Shadow”, 1971, Subseries C, Box: 4, Folder: 39.